Alex Conu: From Amateur to Professional

In our interview series “From Amateur to Professional,” we will be asking established nature photographers to share their photos and see how their practices have developed, changed, and improved over time. You’ll get to see the progression of their images, learn how they got started, and find out how they transitioned from amateur to professional. To see more from this series, subscribe to our free newsletter.

Alex Conu is a photographer based in Oslo, Norway, and is originally from Romania. Besides a degree in photography, Alex also holds a major in astrophysics, thus having a deeper understanding of the astronomical phenomena he photographs. He is a member of TWAN – The World at Night – which is a bridge between art, humanity, and science. He is also the author of The Ultimate Guide to Astrophotography.

When and why did you first catch the nature photography bug?

My field of nature photography is astrophotography. I got into astrophotography first from amateur astronomy. My fascination for the night sky has always been there for as long as I can remember, and I started to do basic astronomical observations when I was maybe 7 years old.

Photography came about three years later, but it was not astrophotography or nature photography. I was just documenting family trips and some other day-to-day stuff. After a while, when I was 12 or 13, I started to merge my two hobbies and actually decided I wanted to have a career as a photographer.

I wanted to be able to share my passion for the night sky with other people. And it was far easier to lure them with photos than to show them some fuzzy small blobs through my telescope.

Show us one of the first images you ever took. What did you think of it at the time compared to now?

I looked through the archives but I was only able to find low resolution files of my first photos. Here’s my first try (and maybe the third photo of the night sky I have ever taken) at photographing the centre of the Milky Way.

It was taken with a Russian made Smena 8M camera, using a homemade barn door tracker. If I remember correctly, the film I used was a cheap Ferrania Solaris 400 ISO. A barn door tracker is made by hinging two pieces of wood together with a piano hinge and aligning that hinge to the celestial pole. To track the apparent motion of the sky, I was supposed to turn a screw once during 60 seconds. It’s quite obvious that tracking was not accurate at all, but that was my first try at it. I got a lot better after a while.

Framing was off, tracking was off… but who cared? I literally started jumping for joy when I saw it printed. I was really amazed to have captured some details in the Milky Way and the outline of the constellation of Sagittarius. Failure is part of the learning process, and I believe this very hands-on approach to astrophotography helped me a lot. This was in 1996 or 1997, and the Internet was not widely available and astrophotography was not exactly as easy to take on as it is today.

Show us 2 of your favourite photos – one from your early / amateur days, and one from your professional career. Tell us why they are your favourites and what made you so proud of them at the time. How do you feel about the older image now that more time has passed?

It’s hard to choose favourites, and it took me a while to select these.

The first one is a photo of the gibbous Moon taken when I was 14. It’s taken through my homemade 150mm Dobsonian telescope, using the afocal method. When shooting afocal, you use the telescope with the eyepiece on and the camera with the lens on. It’s basically like taking a photo with your smartphone through the eyepiece of a telescope.

But there were no smartphones in 1998. This was developed and enlarged by yours truly. I was super happy to be able to go through the whole process, from taking the photo to enlarging the negative, on my own. And I love this photo to this day. I still remember it slowly appearing on the photography paper as it developed.

The second image was taken five years ago. It’s a panorama of the night sky above Cathedral Cove in Coromandel, New Zealand. That’s my first encounter with the Southern stars. I can’t describe the emotions I had when the two Magellanic Clouds became visible, towards the end of twilight.

It was not only the sky that amazed me that night, but also the sea. All the electric blue patches on the ocean are actually bioluminescence. It’s a panorama stitched from 33 vertical images shot on three rows.

As you can easily observe, I chose my favourite images based on feelings. Not technical perfection, nor the rarity of the event photographed. And I strongly believe that photography (and even astrophotography, which is usually seen as a very gear-heavy field) is not about technicalities – it’s about emotion.

When did you decide you wanted to become a professional photographer? How did you transition into this, and how long did it take?

I decided I wanted to become a professional photographer when I was 13 and I watched a documentary about the famous fashion photographer Helmut Newton. It was aired by a Swedish TV station and I understood almost no words. But I was fascinated. I decided I wanted to become a fashion photographer. Actually, fashion and advertising make up most of my earnings as a professional photographer, with astrophotography only adding a small part.

I don’t really know how I transitioned from amateur to professional photography. I just know that I had this goal set in my head and I did my best to achieve it.

Was there a major turning point in your photography career – a eureka moment of sorts?

In 2016, I was invited to join TWAN – The World at Night – which is a program to create and exhibit a collection of stunning landscape astrophotographs and time-lapse videos of the world’s most beautiful and historic sites against a nighttime backdrop of stars, planets and celestial events. TWAN is a bridge between art, humanity, and science. TWAN is the professional association you want to be in, if you’re an astrophotographer.

Becoming a member of TWAN was a huge step forward in terms of exposure, and it helped a lot with developing the business side of my astrophotography.

The World at Night is a program started in 2007 by a bunch of accomplished astrophotographers, led by Babak Tafreshi. The moment the program was started, I set a goal for myself that one day I will join those amazing photographers that I’ve been always looking up to. Being invited to join TWAN is definitely the highlight of my career as an astrophotographer.

It was this aurora storm, photographed from the top of mount Reinebringen in Lofoten, that led to my being invited to join TWAN. It won the Earth and Sky astrophotography contest in 2016.

Are there any places or subjects that you have revisited over time? Could you compare images from your first and last shoot of this? Explain what changed in your approach and technique.

I believe revisiting subjects is imperative in astrophotography. And that’s why you need a lot of patience. You practically photograph the same thing over and over again. That thing is the sky, and in order to photograph it in an outstanding way, you need to understand how it works.

A lot has changed in astrophotography since I started doing it. The biggest change happened, obviously, when digital cameras became widely available.

But the biggest change in my approach is that now I take a lot less photos than when I switched from film to digital. In the beginning, I was shooting a lot and taking photos from lots of vantage points – not all of them being the best ones. Also, when photographing aurorae, I was taking hundreds of photos every clear night but ended up actually using only very few of them.

I started to work more analytical and shoot only when the aurora was at its best. I also started scouting locations during daytime and trying my compositions before sunset. Basically, now I shoot as if I only had a few shots available on a card and try to make the best of those. This also allows for more time of observing the night sky, which I actually enjoy more.

Also, during the past years, I became more involved in fighting against light pollution and in educating people using astrophotography. And I am not talking here about teaching astrophotography, but by using astrophotography as a tool to educate people. I am involved in a wonderful project in my home country of Romania that offers free online classes to children and youngsters who don’t have access to proper education.

What’s the one piece of advice that you would give yourself if you could go back in time?

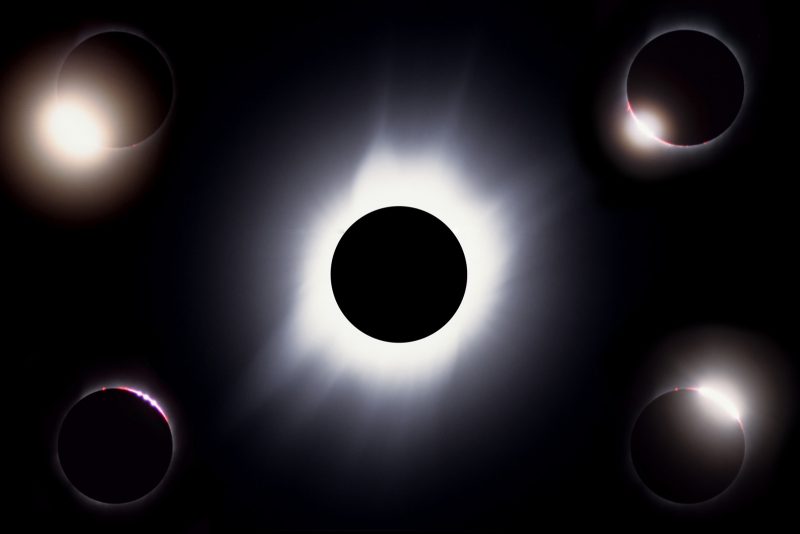

Don’t try to photograph the first total solar eclipse you ever witness. And this is my advice to anyone wanting to photograph a total solar eclipse. If you’ve never seen a total solar eclipse and you prepare for your first one, forget about photography. Just look at it and enjoy the show. It’s something unique that cannot be put into words.

I saw my first total solar eclipse in 1999. I was super enthusiastic and, besides observing it visually, I had decided I also wanted to photograph it. I bought some expensive Kodachrome transparency film and built a contraption from a pair of binoculars to use as a lens. I wasted one minute of totality taking some out of focus shots that were ruined anyway by the photo lab that developed my transparencies using a C-41 process.

This image shows different aspects of totality during the eclipse on March 29th, 2006 – shot on transparency film. Bailey’s beads, Diamond Ring. Prominences, Solar Corona – the total phase of a Solar Eclipse is one of the most astonishing natural phenomena. For a few minutes or seconds (depending on the duration of the total phase), you’re in complete awe. You can’t hear anything, you can’t see anything else but the Sun, and you can’t even move. You have to see a Total Solar Eclipse!

Has anything changed in regards to how you process and edit your images?

If you are talking about changes from what I was doing when I started out and today, a lot has changed. When I started doing astrophotography, digital cameras were not around. There were a few astronomy dedicated CCD cameras, but their price was prohibitive for most amateurs.

When I started, the only edit I was able to do was cropping and colour correcting in the darkroom. But film rendered sky colours in a very accurate way, so there was not a lot to do in that aspect of the editing.

Then, after a few years, I started scanning my negatives and processing was taken to a new level. I believe the biggest step forward at that time was being able to reduce noise.

Then, around 2005, I switched almost completely to digital and it was like discovering a new world. Stacking became a lot easier and, as a result, I was able to show finer details in deep sky objects, that before had been hidden by noise.

But, no matter how my editing process changed, I have always tried to keep colours as close to reality and not go crazy in that area.

What was the most valuable lesson you’ve learnt?

When I started astrophotography, my main goal was to become great at imaging the deep sky. Deep sky photography is about detailed images of galaxies, nebulae, or star clusters.

After some practice, I got quite decent at it and I won some awards in the field and so on. And then I realised those photograph don’t give the average viewer any sense of scale. People were looking at them as if at some oddities, but had no idea how large or small that object was. And, of course, they did not care about all the hours I spent photographing that; actually they shouldn’t care that much, anyway.

Then, I came to the realisation that if I want to get people interested in astronomy, I had to take photos that were easier to relate to. And I switched to photographing almost exclusively nightscapes. That happened when nightscapes were not cool on Instagram.

From a technical point of view, it’s far easier to do landscape astrophotography than hardcore guided deep sky photography. But I believe that in landscape astrophotography your role, as a being capable of feelings, is far more important than in deep sky astrophotography. And that way of doing astrophotography is closer to me.

You can read more about how to photograph the night sky in my book The Ultimate Guide to Astrophotography.

You can visit Conu’s website to see more of his work. For more from this series, subscribe to the free Nature TTL newsletter.